In May 1952, the same month that DNA's double helix

was

first photographed

in Rosalind Franklin's lab, an article appeared in the

Spartanburg Herald-Journal's Peach Edition – extolling

the future of "polyploidy, a scientific method of increasing the quality

of fruit by increasing the number of chromosomes in the

growing cells".

Research had already yielded

"apples twice as heavy and a third larger than standard

varieties".

When this article was written, cytogenetics - the study of

chromosomes' count, size, and shape - was about to enter its midcentury heyday. Japanese

scientists had duplicated rice chromosomes decades earlier, and

Barbara McClintock was identifying transposable elements within

chromosomes, work which would later win a Nobel Prize.

Before I get too deep into history, I should acknowledge that cytogenetics labs are relevant today and karyotyping is used to confirm chromosomal disorders during pregnancy. This page is more about a span of time when cytogenetics was the primary frame to understand genetics, and subject to attention and hype in the media. Looking back, divining information from chromosomes without the ability to zoom in to genes seems so small.

If you are looking for a reference for cytogenetics' timeline, consider the journal Cytogenetics, which became Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics in 1973 and then the modern Cytogenetic and Genome Research in 2001. Or you can look at Google's Ngram Viewer.

Chromosomes stand out

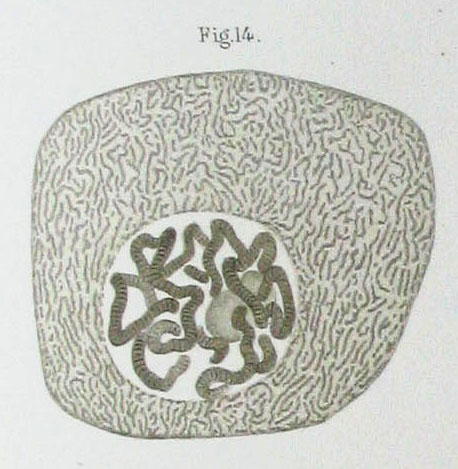

Chromosomes were named in the mid-19th century for their

interesting coloring during staining. By the 1880s

scientists could look at these colorful wormy chromosomes

packed into the nucleus of a cell.

In the early 1900s, scientists reached

a consensus

that chromosomes were the mechanism of genetic inheritance.

Early research identified the X choromosome (1890-1901) and then Y chromosome (1905-1920) related to biological sex. They were noticed for behavior during meiosis, and not named not by shape. Everything was blobby at this point.

Chromosomes become a major topic for scientists and in the

eugenics movement.

In 1925, while announcing a new daughter in the Roosevelt

family, one writer launches into a lesson on chromosome

inheritance finishing with

a prediction: "...with this child, so many wonderful chromosomes are

assembled through every one of her eight great-grandparents,

some of very great worth are bound to be passed on..."

In 1939, chromosomes are covered in the first half of an article

about

inheritance of musical talent.

In 1937, it's discovered that colchicine, an old treatment for

gout, can affect the mitosis of plant seeds and cause a whole

genome duplication (WGD). The resulting plants, with twice as

many chromosomes per cell, sometimes grow larger seeds, grains,

and fruits.

Farmers and gardeners experiment with spraying their plants with

colchicine.

Newspaper articles at the time suggest giant humans could be

coming.

In 1940 the Painesville Telegraph

warns

"

Juggling chromosomes for the betterment of the plant kingdom

is primarily a matter for the trained genetics engineer who

knows the chromosomes with which he is working "

While World War II is beginning in Europe, the US government investigates colchicine's effects to accelerate growth of several crops.

By 1950, botanists have documented the number of chromosomes in

crops as diverse as quinoa and Mexican tea.

They notice the number of chromosomes in varieties of rye have a common multiple, and

that bread wheat is hexaploid - instead of two copies of each chromosome like in humans,

it has six, combining three subgenomes which we now know combined about 9,000 years ago.

Colchicine returns with benefits for

gardens

and

orchards. There are claims about polyploidy in animals, particularly

Albert Levan's

giant rabbits , which are now debunked.

By 1952, researchers suggest images of the chromosomes known as 'karyotypes' or 'karyograms' will be groundbreaking for intersex people "where… the true sex of an individual is in doubt". Before this point, people who were intersex, or otherwise questioning or rejecting the gender assigned at birth, would get their hormone levels measured or request surgical exams, as in the case of civil rights leader Pauli Murray.

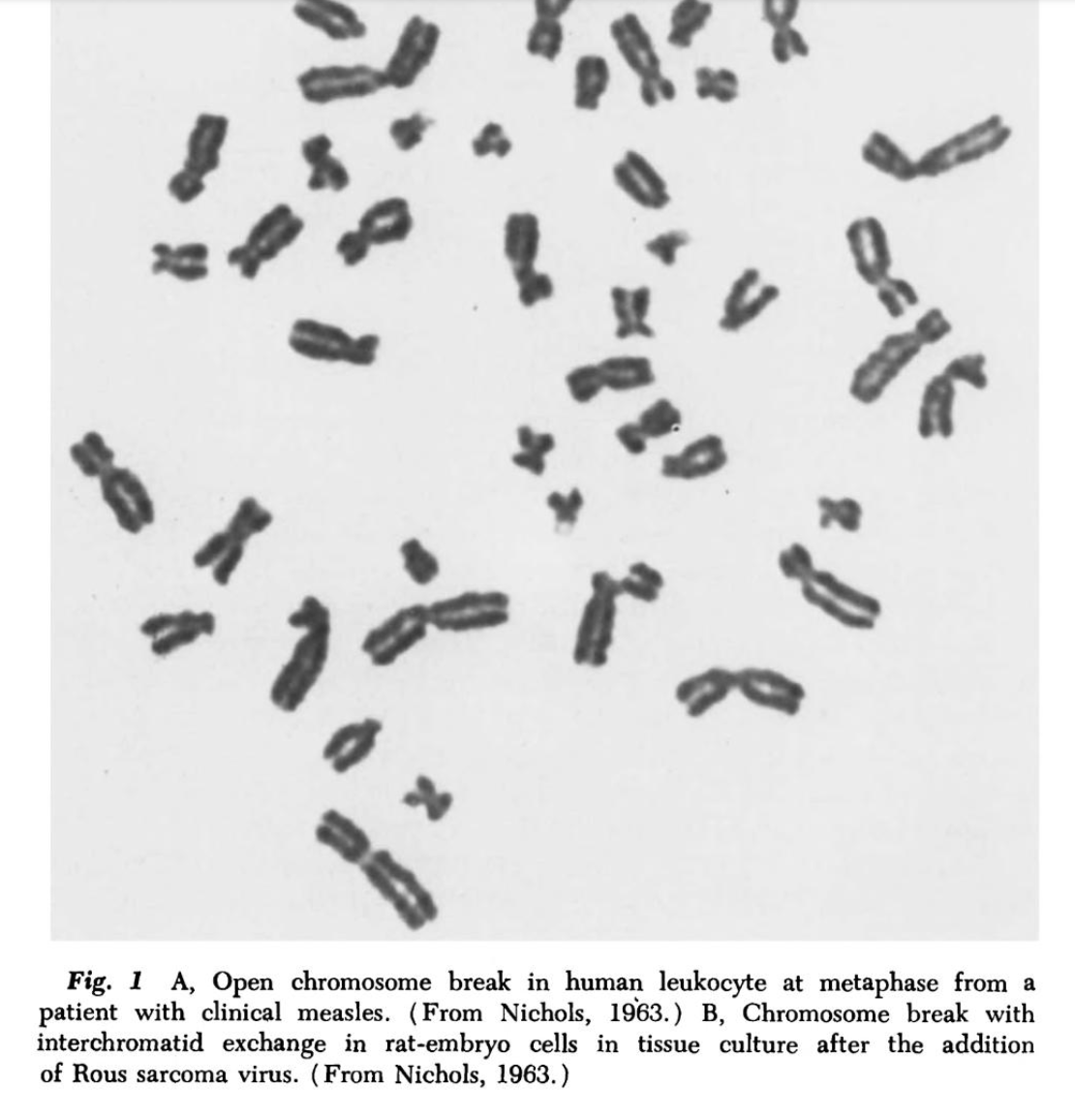

In December 1955 Joe Hin Tjio uses the lab's improvements to Giemsa staining to take the best photograph to-date of chromosomes in metaphase, showing that humans have 46 chromosomes (correcting the count by Theophilus Painter after over 30 years).

Chromosome Damage?

From 1954 onward into the 60s, multiple cytogeneticists

report that the measles virus breaks up chromosomes. Google

will happily summarize these papers' results as current

medical info. I tried to verify if this was still believed

in the present, and

a paper from the 1990s

seems to validate them.

In the late 60s researchers also warn that LSD damages

chromosomes (FDA video,

Daytona Beach Morning Journal article) and that these issues would be passed down to children.

According to

a modern article

in Science News, this was effectively debunked in

1971.

Cancer and the Philadelphia Chromosome

In the 1960s, research continued in earnest on cytogenetics and cancer.

Researchers find a distinctively-shaped "Philadelphia chromosome"

in many cases of leukemia. It takes over 10 years to

identify this as a translocation of material between two

chromosomes, and today we know the specific genes involved.

In 1967, Polish sprinter

Ewa Kłobukowska

is disqualified from participating in an international women's

event based on chromosome results. Reporters at the time speculated on

whether she had

an extra X chromosome

or

mosaicism of X and XYY cells

(Time magazine).

The incident leads the Olympics to adopt a confidential

Barr Body test

to screen athletes at the 1968 Winter Olympics in Grenoble,

France and Summer Olympics in Mexico City.

In 1961 cytogeneticists documented the first patient with XYY chromosomes. Researchers were eager to karyotype institutionalized patients and see if various conditions could be explained with their chromosomes. Allen Bartholomew found multiple Australian prisoners with XYY chromosomes - in 1968 he testified in the trial of Laurence E. Hannell that "every cell in his body and the brain is abnormal". The argument was quickly repeated in cases in Paris, New York, and Los Angeles. Sirhan Sirhan's attorney requests a karyotype test.

Reports in the following year acknowledged that Hannell had other conditions warranting an insanity defense, and chromosomes were mentioned only once in the trial transcript; and a study found XYY "supermales" to instead be less aggressive. By 1971, criminologists reported it as A Modern Myth.

In 1967, the New York Times reports a "Chromosome Service of

the Soviet Union" has been set up, led by

Alexandra Prokofieva-Belgovskaya, "one of the few Soviet scientists qualified to monitor the

chromosome material of the cosmonauts". She was a former target of Stalin's pro-Lysenkoism purges.

A geneticist in Georgia (USA) begins collecting chromosomes from centenarians, hoping that

the karyotypes will indicate how this proneness to longevity is passed from one generation to another

The

New York State Chromosome Registry

launches in 1968. In 1970, the Schenectady Gazette

adds

that registries were recommended by the WHO, and New York's is

managed by the state's Birth Defects Institute.

The

New York Times

later reports

on the foundation of an "Interregional Cytogenetic Register

System".

To me cytogenetics sounds a little like biology's version of

"cybernetics", a field which presaged the path that genomics would take. And its era deserves some more recognition, for both the highs and lows.

I'm struck by the realization that people 50-60 years ago had familiar plans around collecting a genetic database to understand aging and cancer.

A lot of plans and promises like that didn't bear fruit.

Those polyploid

peaches that I opened with

were developed

but quite never made it to Spartanburg. Despite research on their genetics, there don't seem

to have been any commerical GMO peaches yet. Polyploid rice, which

has usually turned out infertile and failed to catch on, is getting reconsidered

with new approaches such as cross-breeding with wild relatives or gene editing.

The swift turnaround from discoveries in cytogenetics to

testing, exclusion, and claims about violence is also

remarkable. Barely a decade after science found the true typical count

of human chromosomes, people were claiming that doctors could predict

someone's criminality or longevity on a karyotype.

That's all that I can think to say about cytogenetics. I don't have

other archival deep dives quite like this, but you could check out my podcast on

Pro Se defendants at the US Supreme Court

if that sounds interesting.

Please do reach out if I can write an article or a script on something!